Industrial policy’s comeback

Industrial policy is experiencing a renaissance. Provoked by multiple crises – financial, climate and health – countries worldwide are seeking to strengthen their economic resilience and shore up their competitive advantages. The conflict in Ukraine, and its impact on supply chains and the cost of living, has made this objective even more critical. The European Union, for example, is investing over EUR 2 trillion in economic recovery and transformation. At the same time, US President Joe Biden has set aside over USD 2 trillion for a “modern American industrial strategy”. The United States and the European Union are not alone. An increasing number of countries across the globe agree that governments need to use industrial policy to strategically address today’s grand challenges.

This new generation of industrial strategies is based on the notion that policymakers must consider both the rate and direction of growth.1 The grand challenges reflected in the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) can serve as a guide to defining growth’s overall direction. These challenges are cross-sectoral by nature and hence we cannot apply a “traditional” vertical approach to them. The resurgent industrial strategy calls for a new toolkit2 based on market shaping and market co-creating across multiple sectors.

Based on well-defined goals – or more specifically “missions” – aimed at solving critical societal challenges, policymakers can steer the direction of growth by coordinating policies across different sectors and by nurturing new industrial landscapes, which the private sector can develop further.3 This “mission-oriented” approach is not about “top-down” planning by an overbearing state; it is about providing direction for growth, guiding business expectations about future growth areas, and catalysing activity that would otherwise not happen.4 It is not about levelling the playing field but about tilting it towards the desired societal goals, such as the SDGs.5

Mission-oriented policy toolkit: the ROAR framework

One key to the success of past market-shaping policies (e.g. the mission-oriented policies of the “moonshot” era), has been to set a clear direction for a problem that needs to be solved (i.e. going to the Moon and back in one generation), requiring cross-sectoral investments and multiple bottom-up solutions, of which some will inevitably fail.6 Too much top-down control can stifle innovation, while too much bottom-up momentum can be dispersive with little impact. A crucial difference between the classical “moonshot” type mission-oriented policies of the cold war era and modern-day missions is that the latter focus on socio-technological challenges, such as decarbonizing food systems.

The policies to address grand challenges should be broad enough to engage the public, enable concrete missions and attract cross-sectoral investment, yet remain focused enough to involve industry and achieve measurable success. By setting the direction for a solution, missions do not specify how to achieve success; instead, they stimulate the development of a range of different solutions to achieve the objective while guiding entrepreneurial self-discovery.7

The figure below summarizes the main questions that a policy framework should try to address (ROAR)8 in order for market-shaping activities to achieve specific missions.

The ROAR framework

The case of solar energy as an enabling factor for innovation-based development in Chile

Mission design requires not only a rethinking of policy logic but also of implementation logic. Current industrial and innovation policies, for instance, are designed and implemented in a waterfall style: new policies often take years to pass through consultation and decision-making processes and are then rolled out in a waterfall moment. Such an approach artificially separates policy design, institutional learning and implementation from each other. On the other hand, missions focus on continuous experimentation to bring forward multiple solutions and foster continuous learning from implementation.

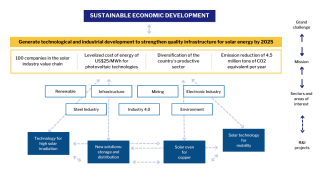

The example of Chile’s strategy for the solar energy sector, which was set up by the Chilean Economic Development Agency (CORFO) in 2016, illustrates the point that missions require the transformation of both policies and organizations in the design and implementation of such policies.9 In its 2025 road map, the Agency aims to promote innovation, develop technologies and skills, and reduce carbon emissions (see next figure).

The Chilean solar industry programme as a mission-oriented policy

Projects implemented under this initiative included the development of technologies to produce energy from high solar irradiation areas (Atacama Desert), new storage and distribution solutions for solar energy, a solar oven for copper production and solar technologies for mobility (the figure below shows the rapid increase in installed solar electricity capacity).

The Chilean solar energy programme employed multiple types of instruments, including an open innovation platform to facilitate the emergence of bottom-up solutions, the creation of technical standards tailored to desert conditions, and the establishment of a new technology institute to facilitate collaboration for clean technology development.

Mobilizing multiple industries and stakeholders is a key feature of mission-oriented policies.10 This is the case even for policies seemingly focusing on individual industries like the Chilean solar industry. Two new instruments were designed to facilitate coordination between different actors and sectors: an open platform to facilitate co-creation and information-sharing, and a clean technology institute to foster cross-disciplinary research for solar energy. The open platform allowed for a bottom-up participatory process, resulting in the development of a shared vision. Platforms increase trust between public and private stakeholders and help identify technical and economic challenges that warrant public support.

Another recurring structure for coordination is the establishment of multi-stakeholder committees. In the Chilean solar case, CORFO, the Ministry of Economy and the Ministry of Energy created a public–private entity, the Executive Committee, which consists of the solar and energy sectors’ main stakeholders. The Committee’s purpose was to better capture stakeholder demands in the solar sector and determine missions and technological opportunities. Ultimately, such committees contribute to creating the technical and administrative capacity so the state can implement mission-oriented policies.

Transforming public agencies

Future industrial strategies need to be mission-oriented and aim at addressing the grand challenges reflected in the SDGs. This means that the social contract between the public and private sector needs to be re-designed so investment is inclusive and sustainable.11

To effectively address grand challenges, governments need to develop long-term solutions; however, some aspects of these challenges require agile and dynamic responses.12 This paradoxical situation implies that public organizations need to develop frameworks and tools for governments to become more proactive in taking on the multifaceted, long-term issues societies face.

Future industrial strategies thus require public agencies that are both dynamic and resilient.13 These agencies need more citizen engagement in the design and delivery of public services. By incorporating new analytical frameworks, methods and analytical tools, such as strategic design, complexity economics, foresight and policy labs, these agencies can focus on continuous engagement and learning.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this article are those of the authors based on their experience and on prior research and do not necessarily reflect the views of UNIDO (read more).

Have your say

What is your opinion on the IAP?