History has shown that coordination, cooperation and the mobilization of scientific and technological progress combined with strong manufacturing capabilities are critical for addressing complex challenges. In July 1945, Vannevar Bush, the Director of the Office of Scientific Research and Development, handed then-President Truman a report on the substantial contribution of science to the Allies’ victory in the Second World War.1 The report praised “many of our scientists [who] have been fighting the war in the laboratories, in the factories and shops”, and emphatically acknowledged scientific progress as an essential key to a nation’s security, improved health, jobs, a higher standard of living and cultural progress. Bush’s recommendations to the United States government resulted, among others, in the establishment of the National Science Foundation, while setting the stage for a more structured national approach towards science, technological development and coordination between actors in the science and technology system. More importantly, Bush’s report became the cornerstone of modern science policy, and it continues to influence the governance of scientific enquiry today.2

As the modern world is grappling to deal with the COVID-19 outbreak, science, technology and innovation (STI) are back in the trenches, helping us understand the biology of the virus, informing strategies to contain it, and contributing possible solutions to dealing with the virus’s potentially pernicious health, social and economic effects. Manufacturing also plays an important role, both as a source of solutions to the pandemic and as a sector that will suffer major setbacks in terms of level of activity and job losses.

Revisiting some of Bush’s core tenets seems useful to guide our reflections on how developing countries can inform their response to COVID-19 with a view towards recovery and long-term resilience. Four aspects are particularly relevant in this regard, namely: (1) STI contributes to addressing health challenges; (2) STI underpins the development of new products, new industries and jobs; (3) dynamic STI systems entail strong and effective collaboration and coordination between actors in the system; and (4) a well-performing STI system requires active public policy support.

First, there is the issue of health

Bush highlights scientific progress as a driver of good health during extreme events such as wars or, as is currently the case, disease outbreaks. Santiago et al. (2020) explore different ways STI contributes to managing the health emergency. Bush likewise acknowledged the contribution of research to address structural health problems. COVID-19 penalizes countries with long overdue investments in their healthcare system, and further exacerbates poverty and inequalities. As countries begin to reopen their economies, their medium- to long-term recovery plans should pay greater attention to industrial organization challenges associated with public health beyond immediate responses to emergent diseases. Innovative solutions and redesigned global regulatory supply chain frameworks are necessary to enhance resilience and transform health challenges into longer-term industrial development opportunities, particularly in developing countries.3

There is more to economic progress than science

The world has changed considerably since the publication of Bush’s findings; for one, our understanding of the relationship between social and economic development and STI has evolved. STI’s fundamental contribution to the global development agenda remains steadfast.4 Modern STI notions recognize the interrelated nature of these activities and their distinct logics of operation in terms of knowledge creation, mobilization and use. Innovation, in particular, involves capacity-building and multi-stakeholder interactions; under the right conditions, it contributes to the generation of new products, new industries and creates additional jobs. Manufacturing remains the locus of innovation.

One lesson the pandemic has taught us is that we need to identify and invest in strategic sectors to safeguard sovereignty in times of temporary global value chain disruptions. Governments from both developed and developing countries have implemented measures to support industries to retool their activities and switch their production to the manufacturing of masks, ventilators, testing equipment, hand sanitizer and other products essential for dealing with COVID-19. This, however, is only possible if firms possess a certain level of production and innovative capabilities, which in turn presupposes accumulated investments in the development of STI capacities at different levels.

Collaboration and cooperation

Bush emphasizes the need for cooperation and coordination between civilian scientists and the military. The current COVID-19 pandemic underscores the need for strong coordination and cooperation across sectors not only within countries, but also between countries. Despite rising trade and diplomatic tensions between the United States and China, for example, a study by Dataverz for Axios, a data analytics start-up in Copenhagen, finds that nearly 407 papers published this year alone have been co-authored by researchers from American and Chinese institutions. This represents around 5.2 per cent of roughly 7,770 studies published by researchers from the two countries.5 The analysis included mostly pre-print papers for 2020. Scientists are currently collaborating on testing COVID-19 treatments and drug candidates, developing vaccines and trying to uncover the origin and spread of SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19.

Latin American countries are mobilizing domestic scientific and technological capabilities to deal with COVID-19 by building on multi-stakeholder interactions. These experiences should inform necessary interventions to foster greater interactivity and STI efforts to fight other prevalent diseases such as dengue or measles. More importantly, the experiences made in health and biological sciences should be replicated in other strategic areas where industrial innovation and industry-academic interactions can play an instrumental role, for example, in food security, energy sustainability and environmental degradation.

Public policy is necessary for STI to contribute to development

The post-war period witnessed the establishment of specialized organizations to promote science and technology, such as UNESCO, as well as several specialized science policy structures in much of the developing world.6 The upshot? Greater political attention and a more systematic infusion of resources to science and technology and related infrastructures in developing countries.7 Long-term STI programmes require a sufficient and stable stream of resources. Unfortunately, commitment to supporting STI — captured by the overall expenditure in R&D relative to GDP — and to using it as a driver of industrialization falters in most developing countries. Donor support should supplement, rather than substitute, domestic investments in R&D (particularly by industry), human resources development and strengthened infrastructure and governance of innovation systems at different levels.

While the pandemic may have given rise to new and sometimes perilous challenges for the state of global socio-economic affairs, it has also opened new policy opportunities to revisit national and cross-national approaches to STI and to collaboration and coordination within the STI system. While inclusivity and sustainability have been high on the global agenda for years, such abstract concepts are often challenging for many developing countries to implement.8 The COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted that practice informs policies, rather than vice versa, in terms of concretizing these two development approaches. Several firms have done an about-turn amid the pandemic, and have implemented inclusive and sustainable business models as a means of supporting both local and global communities and are now producing essential goods necessary to deal with COVID-19. Tesla and LVMH, for example, usually only offer highly exclusive products, but in the midst of the current crisis have proven their capacity and willingness to promote the mandate of inclusiveness and sustainability. Policymaking could capitalize on the social and business flexibility of resource rich firms as we move forward from the COVID-19 crisis.

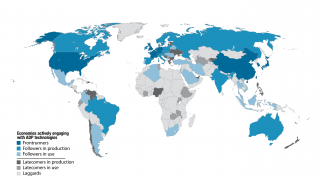

However, we must recognize the fact that the distribution of challenges and opportunities across countries is anything but even. Divergence is evident if one considers the participation of firms, particularly small and medium sized companies, in the Fourth Industrial Revolution (4IR). The figure below illustrates the high level of heterogeneity that characterizes the adoption of different generations of digital technologies across countries, with significantly lower levels among firms in low- and middle-income countries; moreover, the ability to produce core 4IR remains heavily concentrated in a handful of countries and firms around the world.9

Productive diversification through STI should furthermore aim to enhance resilience and reduce exposure to external shocks. The pandemic has battered the apparel industry, for example, which is the manufacturing lifeline of several developing countries from Africa to Asia, and concentrates considerable efforts in accumulating industrial capabilities to upgrade and enter the apparel global value chain. Apparel-centric institutions may be at a loss about what to do with their very specialized set of capabilities and skills, and how to repurpose these. Governments may also be forced to reopen apparel factories much too soon, putting workers at risk. Similar debates are currently taking place in Mexico’s automobile industry.

While countries begin to realign their STI policies to meet the mark on health management and industrial development in a post-COVID-19 world, we must continue to foster the debate on revisiting existing roadmaps for capacity-building in developing countries, and attend to their differentiated needs and challenges.

The current COVID-19 outbreak is a reminder that we need to be prepared to respond to complex situations and emergencies. While the ability to respond promptly depends on countries’ STI capacities — which countries need to develop from within — government must foster investment in the skills of the young population so they can accumulate, translate and enhance their knowledge. This can be achieved by creating robust research infrastructure, provide sufficient funding and incentives and set up frameworks within which STI can be carried out. The time is now or never. Active and strategic investments in STI capacities should also link to the development of strategic industries defined in accordance with pressing development challenges. Policies to enhance collaboration and partnerships among sectors in the post-COVID-19 world should be part of a country’s core strategies to put knowledge into productive use.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this article are those of the authors based on their experience and on prior research and do not necessarily reflect the views of UNIDO (read more).

Have your say

What is your opinion on the IAP?